client: Harrahs Entertainment, Inc.

improvement: Don’t Worry, Be Happy

date: January 10, 1990

San Francisco Bay Guardian

January 10, 1990

Free the Billboards!

They’re professional. They’re organized, They’re out to pave Alaska — and they believe that out door advertising is too important to be left to a few big billboard companies. Behind the scenes with the Billboard Liberation Front

By Tim Redmond

“Don’t Try this at Home” (intro to main article)

“Roscoe Meets the BLF” (sidebar of main article)

THE CALL fame in on a Monday, a little after midnight. The publicists and bill collectors have usually given up by that hour, so I figured it must be someone I know and picked up the phone.

“Is this Tim Redmond?” asked an unfamiliar voice. “Yes,” I said slowly, kicking myself for taking the call.

“This is Jack,” the caller said. “Jack Napier. From the BLF.”

Right. Jack Napier. The BLF. I closed my eyes and tried to make my memory work through the deadline-night bourbon-and-beer-for-dinner haze. The Brothers of Love Family? The Black Lung Foundation? The Bourgeois Lunatic Fringe?

I tried not to sound baffled. “OK,” I said. “I’m listening.”

“Look out your front window,” the caller continued. “Across the street from your house is a building with two stone pillars. On the back of the pillar on the right, about three fat above the ground, you will find an envelope containing your instructions. Please retrieve it immediately. We’ll be in touch.”

He hung up, and I looked out the window. Yeah, that building had something that could pass for a pair of stone pillars. I walled across the street and started feeling around the back side of my neighbor’s pillar.

And yes, indeed, there was an envelope on the back, attached with about seven rolls worth of masking tape. I managed to pry it loose (with only a minor loss of blood, skin and fingernails) and ran back inside to tear it open.

And suddenly, it all became perfectly clear. The midnight call. The secret mail drop. The mysterious name (borrowed, I later realized, from Batman). This was no ordinary organization: I was dealing with the Billboard Liberation Front.

WE GET a lot of press releases at the Bay Guardian. Most of them describe past or upcoming events, contain statements by some group or individual or present the exciting and novel facts about some product or service that some publicity consultant is trying to hype. Normally they include at least basic information for contacting the key individuals involved — like an address and phone number.

But the press packet that came across my desk in May was of a different type altogether. The centerpiece was a standard color snapshot of a Kearney Street billboard that had once promoted a radio station with the slogan “HITS HAPPEN — NEW X-100.” In its new incarnation, the billboard read like this:

“SHIT HAPPENS — NEW EXXON.”

This was no random graffiti-in-the-night job. It was unquestionably professional work — the letters on the new panels were virtually identical to the originals. And it summed up nicely Exxon’s response to the Alaska oil spill.

The folks who “liberated” the radio billboard explained their views in a statement wrapped around the photo: “One of the primary goals of the Billboard Liberation Front has always been to encourage and accelerate the ongoing paving of the world,” it stated. “For, as we all know, where there are no roads, there are no billboards. Exxon and other fine corporations contribute to this necessary evolution process through many methods, including the use of petrochemicals in the production of asphalt.

“We at the BLF say…Pave Alaska!”

Pave Alaska: Now there was a novel idea. I scoured the press materials for an address or contact number. Nothing. I dug the envelope out of the garbage and looked for a return address. Nothing.

It wasn’t until I had gone over the stuff a second and third time that I noticed a small line at the bottom of the last page: “To contract the BLF,” it said, “please leave a classified ad in the Bay Guardian ‘Spirituality’ category. You will hear from us.”

It took several weeks for a guy named Jack Napier (remember the Joker’s alter ego?) to reach me at the office. I told him I’d love to meet with him and his colleagues, at their convenience. “I don’t know,” he said. “We know your newspaper doesn’t support our political positions. We know you radical environmentalists love to attack the big corporations like Exxon that we’re trying to defend. We have to wonder whether you’re objective enough to do I fair story on us.”

I swore I was the very essence of an objective reporter, that I had no particular political beliefs of my own, that I was simply a cog in the machine, doing my job like everyone else. I swore I bought all my gas from Exxon and let as much as I could leak out of the motorcycle and onto the street. He said he didn’t believe me, but would take my offer to the leadership. I thanked him, shook my head and promptly forgot all about it.

SO I HAVE to admit that when the late-night missive with the BLF letterhead arrived a couple of months later, I let my objectivity slip. I was excited.

“Your code name for this operation will be Mr. Roscoe,” the message read. “Be at Bouncers bar at 7:15 Friday night. Order a gin and sit near the phone booth inside the bar. Wait for our call.

“Please be alone and do not attempt to have anyone follow you.”

I had my first interview with BLF members that night, in a garage some where in the central Bay Area. I was brought there blindfolded, in the back of a van, after a lengthy saga of pay phones, cryptic messages and obscure letter drops in places like the towel dispenser of a portable toilet outside the Navy base at Treasure Island (see sidebar).

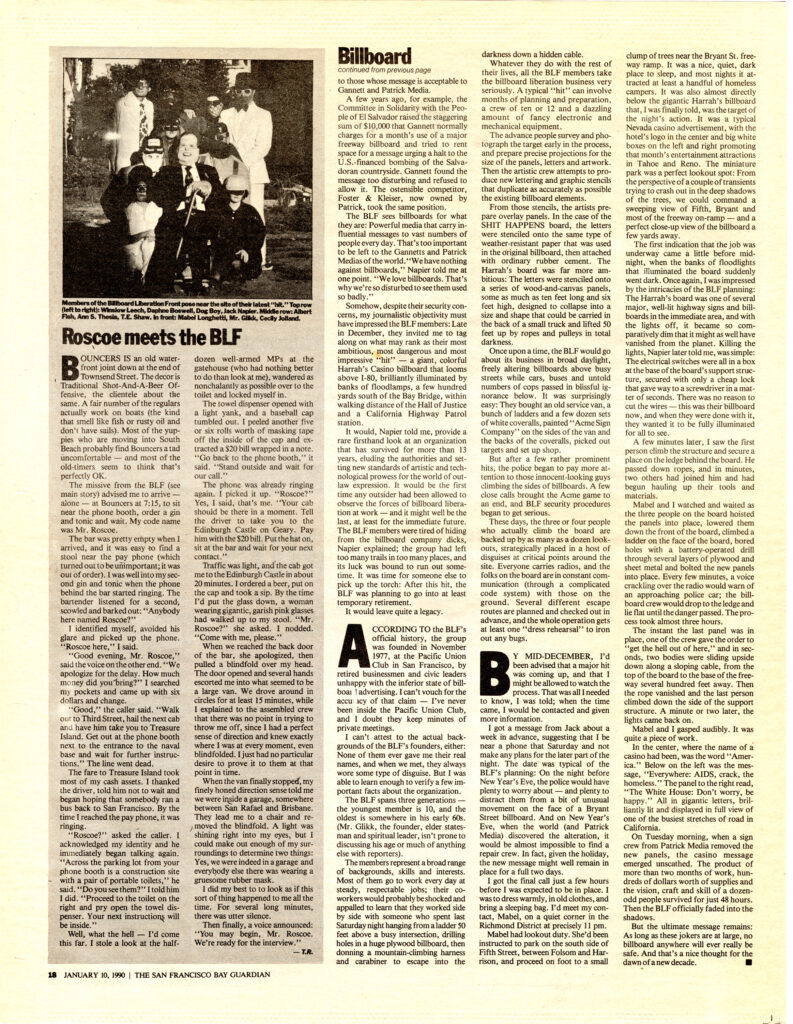

There were about 15 people at that meeting, representing most of the current active membership. They had names like Daphne Boswell, Igor Pflicht and Mr. Glikk, and all of them wore some type of gruesome rubber mask. (One repeatedly brandished rifle and shouted menacing words in a language I couldn’t identify; I was later told his name was Walid Rasheed, and that he’d left the PLO when he decided it had become too wimpy. “But don’t worry,” Napier reassured me. “He’s really very friendly when you get to know him.”)

Over the next few months, I met several more times with smaller groups, always at random locations arranged through last-minute phone calls or secret mail drops. The folks in the BLF obviously enjoyed the whole cloak-and-dagger game, but there was a very serious side to it, too: They’ve been altering billboards in the Bay Area since 1977, Napier explained, and Gannett and Patrick Media, the two giant companies that control most of the local billboard industry, were not at all happy about it. The BLF members are convinced that Gannett and Patrick have hired private detectives to find the free-speech terrorists and bring them to justice.

And beyond the deranged press releases, there’s also a very serious side to the BLF’s mission. In 1990, a very small number of very big corporations (Gannett is one of the biggest) own the vast majority of the nation’s information sources. They control the flow of political and cultural information, the messages that shape the way most Americans think about the world around them.

In theory, billboards are a purely commercial enterprise; space is available for rent to anyone who can fork over the cash. In practice, the space is open only to those whose message is acceptable to Gannett and Patrick Media.

A few years ago, for example, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador raised the staggering sum of $10,000 that Gannett normally charges for a month’s use of a major freeway billboard and tried to rent space for a message urging a halt to the U.S.-financed bombing of the Salvadoran countryside. Gannett found the message too disturbing and refused to allow it. The ostensible competitor, Foster & Kleiser, now owned by Patrick, took the same position.

The BLF sees billboards for what they are: Powerful media that carry influential messages to vast numbers of people every day. That’s too important to be left to the Gannetts and Patrick Medias of the world. “We have nothing against billboards.” Napier told me at one point. “We love billboards. That’s why we’re so disturbed to see them used so badly.”

Somehow, despite their security concerns, my journalistic objectivity must have impressed the BLF members: Late in December, they invited me to tag along on what may rank as their most ambitious, most dangerous and most impressive “hit” — a giant, colorful Harrah’s Casino billboard that looms above 1-80, brilliantly illuminated by banks of floodlamps, a few hundred yards south of the Bay Bridge, within walking distance of the Hall of Justice and a California Highway Patrol station.

It would, Napier told me, provide a rare firsthand look at an organization that has survived for more than 13 years, eluding the authorities and setting new standards of artistic and technological prowess for the world of outlaw expression. It would be the first time any outsider had been allowed to observe the forces of billboard liberation at work — and it might well be the last, at least for the immediate future. The BLF members were tired of hiding from the billboard company dicks, Napier explained; the group had left too many trails in too many places, and its luck was bound to run out sometime. It was time for someone else to pick up the torch: After this hit, the BLF was planning to go into at least temporary retirement.

It would leave quite a legacy.

ACCORDING TO the BLF’s official history, the group was founded in November 1977, at the Pacific Union Club in San Francisco, by retired businessmen and civic leaders unhappy with the inferior state of billboard advertising. I can’t vouch for the accuracy of that claim — I’ve never been inside the Pacific Union Club, and I doubt they keep minutes of private meetings.

I can’t attest to the actual backgrounds of the BLF’s founders, either: None of them ever gave me their real names, and when we met, they always wore some type of disguise. But I was able to learn enough to verify a few important facts about the organization.

The BLF spans three generations — the youngest member is 10, and the oldest is somewhere in his early 60s. (Mr. Glikk, the founder, elder statesman and spiritual leader, isn’t prone to discussing his age or much of anything else with reporters).

The members represent a broad range of backgrounds, skills and interests. Most of them go to work every day at steady, respectable jobs; their co-workers would probably be shocked and appalled to learn that they worked side by side with someone who spent last Saturday night hanging from a ladder 50 feet above a busy intersection, drilling holes in a huge plywood billboard, then donning a mountain-climbing harness and carabiner to escape into the darkness down a hidden cable.

Whatever they do with the rest of their lives, all the BLF members take the billboard liberation business very seriously. A typical “hit” can involve months of planning and preparation, a crew of ten or 12 and a dazzling amount of fancy electronic and mechanical equipment.

The advance people survey and photograph the target early in the process, and prepare precise projections for the size of the panels, letters and artwork. Then the artistic crew attempts to produce new lettering and graphic stencils that duplicate as accurately as possible the existing billboard elements.

From those stencils, the artists prepare overlay panels. In the case of the SHIT HAPPENS board, the letters were stenciled onto the same type of weather-resistant paper that was used in the original billboard, then attached with ordinary rubber cement. The Harrah’s board was far more ambitious: The letters were stenciled onto a series of wood-and-canvas panels, some as much as ten feet long and six feet high, designed to collapse into a size and shape that could be carried in the back of a small truck and lifted 50 feet up by ropes and pulleys in total darkness.

Once upon a time, the BLF would go about its business in broad daylight, freely altering billboards above busy streets while cars, buses and untold numbers of cops passed in blissful ignorance below. It was surprisingly easy: They bought an old service van, a bunch of ladders and a few dozen sets of white coveralls, painted “Acme Sign Company” on the sides of the van and the backs of the coveralls, picked out targets and set up shop.

But after a few rather prominent hits, the police began to pay more attention to those innocent-looking guys climbing the sides of billboards. A few close calls brought the Acme game to an end, and BLF security procedures began to get serious.

These days, the three or four people who actually climb the board are backed up by as many as a dozen lookouts, strategically placed in a host of disguises at critical points around the site. Everyone carries radios, and the folks on the board are in constant communication (through a complicated code system) with those on the ground. Several different escape routes are planned and checked out in advance, and the whole operation gets at least one “dress rehearsal” to iron out any bugs.

BY MID-DECEMBER, I’d been advised that a major hit was coming up, and that I might be allowed to watch the process. That was all I needed to know, I was told; when the time came, I would be contacted and given more information.

I got a message from Jack about a week in advance, suggesting that I be near a phone that Saturday and not make any plans for the later part of the night. The date was typical of the BLF’s planning: On the night before New Year’s Eve, the police would have plenty to worry about — and plenty to distract them from a bit of unusual movement on the face of a Bryant Street billboard. And on New Year’s Eve, when the world (and Patrick Media) discovered the alteration, it would be almost impossible to find a repair crew. In fact, given the holiday, the new message might well remain in place for a full two days.

I got the final call just a few hours before I was expected to be in place. I was to dress warmly, in old clothes, and bring a sleeping bag. I’d meet my contact, Mabel, an a quite corner in the Richmond District at precisely 11 pm.

Mabel had lookout duty. She’d been instructed to park on the south side or Fifth Street, between Folsom and Harrison, and proceed on foot to a small clump of trees near the Bryant St. freeway ramp. It was a nice, quiet, dark place to sleep, and most nights it attracted at least a handful of homeless campers. It was also almost directly below the gigantic Harrah’s billboard that, I was finally told, was the target of the night’s action. It was a typical Nevada casino advertisement, with the hotel’s logo in the center and big white boxes on the left and right promoting that month’s entertainment attractions in Tahoe and Reno. The miniature park was a perfect lookout spot: From the perspective of a couple of transients trying to crash out in the deep shadows of the trees, we could command a sweeping view of Fifth, Bryant and most of the freeway on-ramp — and a perfect close-up view of the billboard a few yards away.

The first indication that the job was underway came a little before midnight, when the banks of foodlights that illuminated the board suddenly went dark. Once again, I was impressed by the intricacies of the BLF planning: The Harrah’s board was one of several major, well-lit highway signs and billboards in the immediate area, and with the lights off, it became so comparatively dim that it might as well have vanished from the planet. Killing the lights, Napier later told me, was simple: The electrical switches were all in a box at the base of the board’s support structure, secured with only a cheap lock that gave way to a screwdriver in a matter of seconds. There was no reason to cut the wires — this was their billboard now, and when they were done with it, they wanted it to be fully illuminated for all to see.

A few minutes later, I saw the first person climb the structure and secure a place on the ledge behind the board. He passed down ropes, and in minutes, two others had joined him and had begun hauling up their tools and materials.

Mabel and I watched and waited as the three people on the board hoisted the panels into place, lowered them down the front of the board, climbed a ladder on the face of the board, bored holes with a battery-operated drill through several layers of plywood and sheet metal and bolted the new panels into place. Every few minutes, a voice crackling over the radio would warn of an approaching police car; the billboard crew would drop to the ledge and lie flat until the danger passed. The process took almost three hours.

The instant the last panel was in place, one of the crew gave the order to “get the hell out of here,” and in seconds, two bodies were sliding upside down along a doping cable, from the top of the board to the base of the freeway several hundred feet away. Then the rope vanished and the last person climbed down the side of the support structure. A minute or two later, the lights came back on.

Mabel and I gasped audibly. It was quite a piece of work.

In the center, where the name of a casino had been, was the word “America.” Below on the left was the message, “Everywhere: AIDS, crack, the homeless.” The panel to the right read, “The White House: Don’t worry, be happy.” All in gigantic letters, brilliantly lit and displayed in full view of one of the busiest stretches of road in California.

On Tuesday morning, when a sign crew from Patrick Media removed the new panels, the casino message emerged unscathed. The product of more than two months work, hundreds of dollars worth of supplies and the vision, craft and skill of a dozen odd people survived for just 48 hours. Then the BLF officially faded into the shadows.

But the ultimate message remains: As long as these jokers are at large, no billboard anywhere will ever really be safe. And that’s a nice thought for the dawn of a new decade.